Dr. Changde Cheng

Assistant Professor

Stem Cell Biology | Cancer Outcomes and Survivorship | Biomedical Informatics and Data Science

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Research Focus

Therapy Design and Engineering

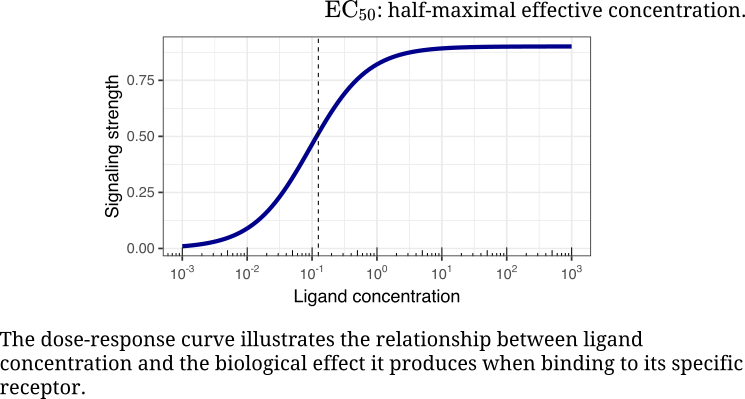

We design and engineer combination therapies by mapping epistasis, inferring causal control, and using mechanism-informed computational methods to translate molecular logic into therapy. Yet one question keeps returning: how is control itself written into the language of cells? How do ligand–receptor dynamics give rise to coordination and integration?

Evolution, Genetics, and Disease

Males and females share nearly identical genomes, yet they differ in how they look, function, and respond to disease. I often wonder why those differences exist and how they shape health, how the push and pull of sex-biased selection over deep time leaves marks that echo in modern medicine.

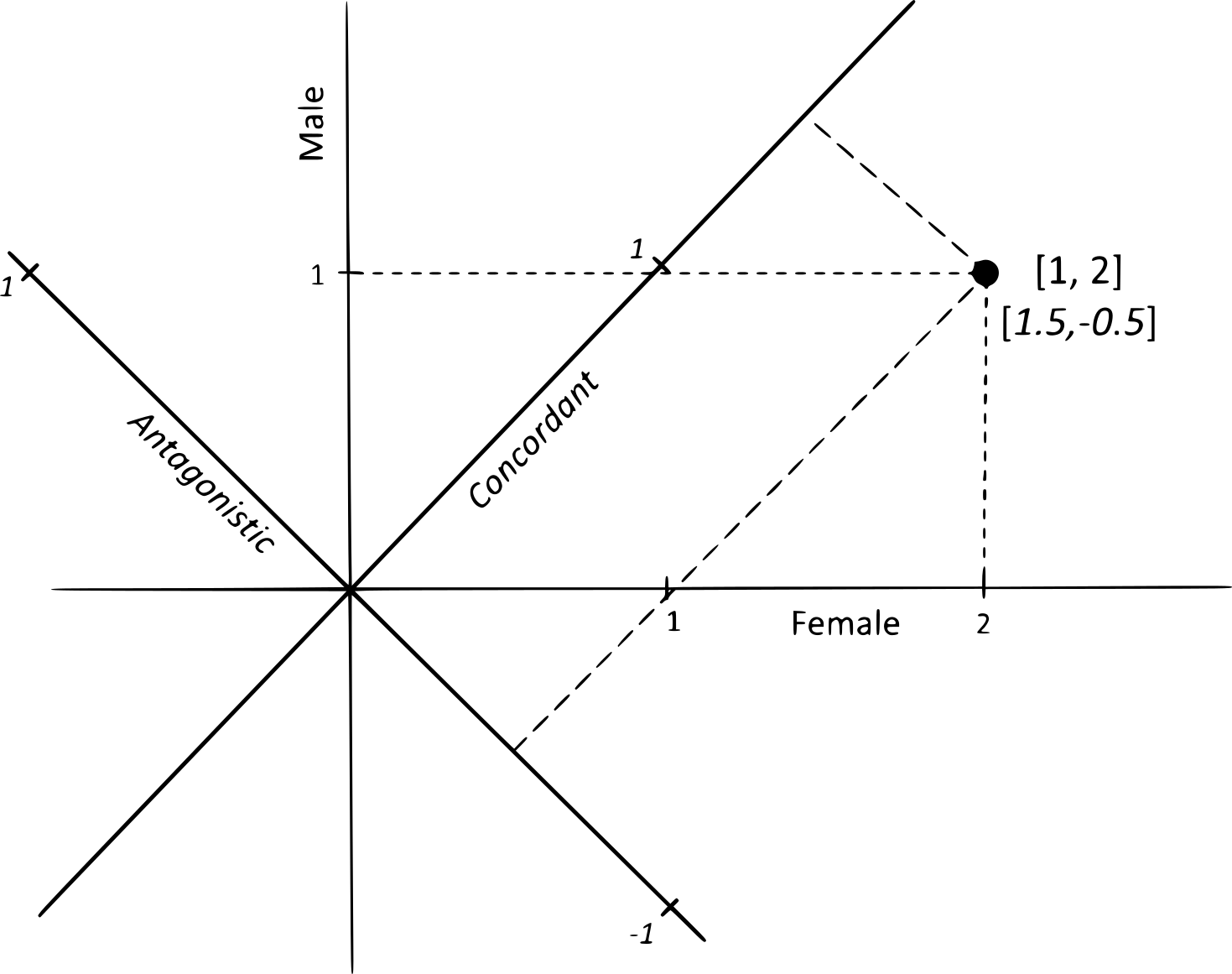

How do sexually concordant and discordant forms of selection interact to mold genomes and traits? Concordant selection moves both sexes in the same direction, while discordant selection favors one at the expense of the other, creating evolutionary tension that leaves a lasting signature on the genome:

Does sexually discordant selection drive the evolution of sexual dimorphism more strongly than sexually concordant selection? David Houle and I have suggested that many cases of sexual dimorphism may in fact arise from concordant selection, rather than from conflict between the sexes. Yet much remains to be explored: how concordant and discordant forces interact, and under what conditions one predominates over the other, remain fascinating questions.

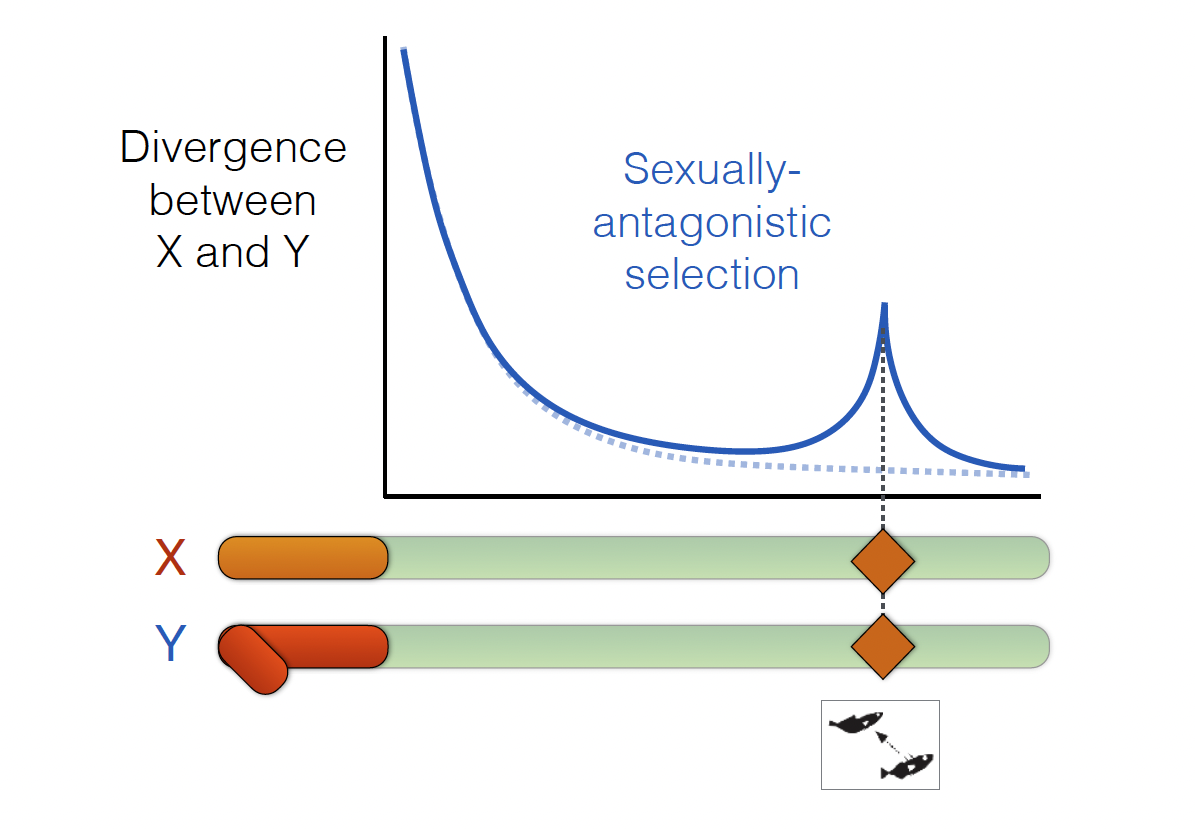

Sex chromosomes have long been regarded as the natural focal points of sexual conflict, where the interests of males and females diverge most sharply:

One question is whether chromosomal inversions act as recombination suppressors that preserve advantageous, sex-specific allele combinations and amplify differences between the sexes.

How flexible are these differences between the sexes? I’m fascinated by how environmental plasticity reshapes sex-biased gene expression and shifts the correlation between male and female expression, allowing organisms to navigate the tug-of-war between male-optimal and female-optimal states.

How does aging reshape evolution’s balance of forces? As purifying selection weakens, late-acting mutations, and sex differences in disease, grow more visible. With Mark Kirkpatrick, I examined how the force of natural selection changes over the lifespan and how this affects the molecular evolution of genes. We found that mutations expressed late in life are less efficiently removed, with shorter genomic lifespans, consistent with theoretical predictions about how aging evolves through the weakening of selection.

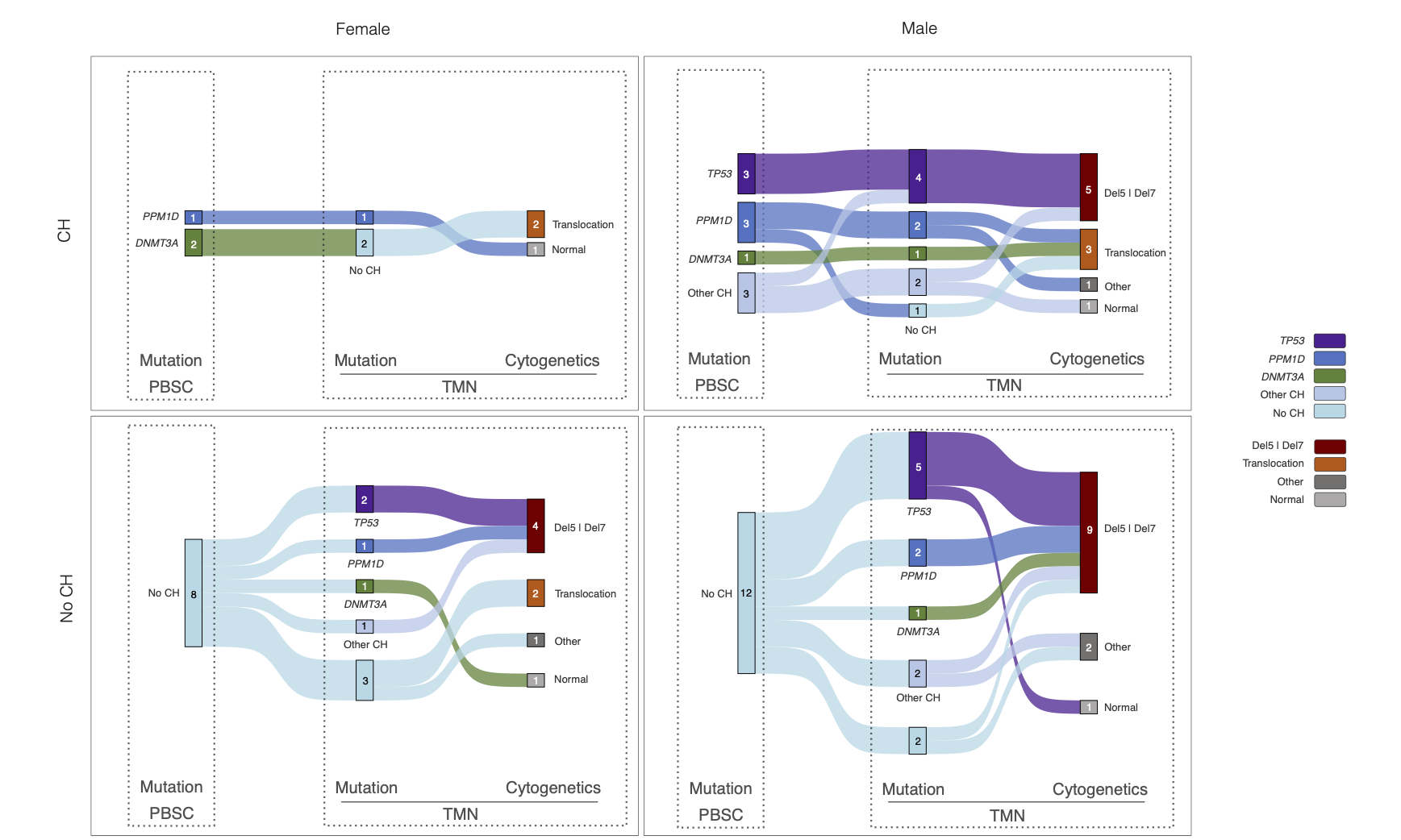

These ideas motivate my current analyses of clonal evolution in hematopoietic stem cells after cancer therapy. Many patients develop clonal hematopoiesis, in which mutations arise and a subset of stem-cell clones expands. In our cohort, clonal hematopoiesis occurs in 37.2% of patients, with similar incidence in males (35.8%) and females (39.6%), and recurrently involves the same genes in both sexes, including DNMT3A, PPM1D, TET2, and TP53. The subsequent trajectories diverge: in males, mutated clones expand more often and progress to therapy-related blood cancers in 12.4% of cases, whereas progression in females is 3.6%.

Mutations persist, expand, or disappear during disease progression, associated with specific chromosomal abnormalities across biological groups.

These patterns suggest that selection on clones is sex-conditioned. Comparable genetic starting points can yield different outcomes because the surrounding biology, hormonal milieu, immune surveillance, stromal niches, and epigenetic states, reshapes fitness landscapes in sex-specific ways. My model aims to identify which components shift a clone from benign passenger to malignant driver, and how those components change with age.

Sexual discordance is not a theoretical curiosity confined to sex chromosomes but a living force that shapes disease. By connecting evolutionary principles to measurable cellular mechanisms, we seek to improve risk prediction, refine surveillance, and design therapies that remain effective within the sex-specific and age-dependent constraints imposed by evolution.

Adaptation, Speciation, and Infectious Disease

My early work centered on a classical question: how do chromosomal inversions shape adaptation and divergence? This inquiry soon led to a more applied one: how do these same inversions influence disease transmission in malaria mosquitoes? In pursuing these questions, I challenged the prevailing “speciation island” model, showing instead that genomic divergence arises primarily from regions of suppressed recombination.

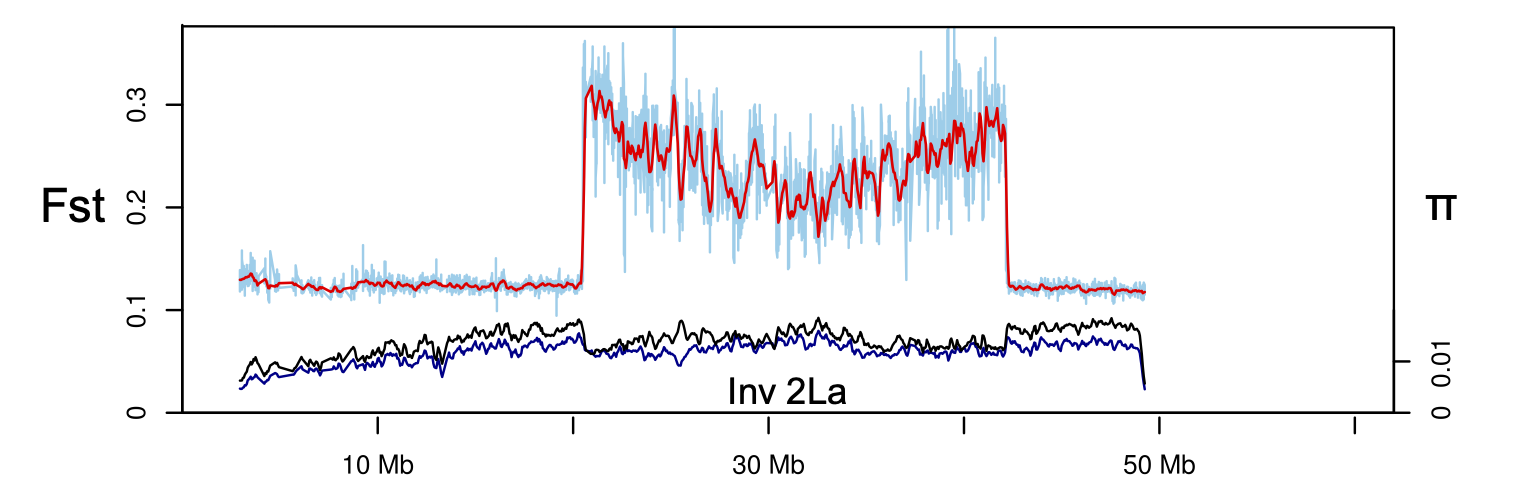

Using Anopheles gambiae as a model, I found that inversion 2La tracks Africa’s aridity gradient and forms a suspension-bridge pattern of differentiation, confirming that inversions capture locally adapted alleles by suppressing recombination.

Laboratory and transcriptomic analyses further revealed that inversions shape multiple traits, including fecundity, longevity, behavior, and stress tolerance, through interactions with environment and sex. In Anopheles, such structural variation links ecological adaptation with the evolution of vectorial capacity, showing how genomic architecture organizes both ecological and epidemiological diversity.

In Genetic association of physically unlinked islands of genomic divergence, I re-examined the “speciation island” hypothesis. The near absence of gene flow between incipient species suggests that highly diverged pericentromeric regions, marked by low variation and recombination, may be incidental rather than instrumental to speciation—an insight that reframed how genomic divergence and population structure are interpreted in the early stages of species formation.

These findings connect population genetic theory with ecological and epidemiological dynamics. In malaria mosquitoes, inversions not only stabilize local adaptation but also modulate vectorial capacity, illustrating how genomic architecture organizes both ecological and disease-related diversity.